In the last 200 years, humans have sent rockets to Jupiter, the Internet has transformed communication, the Human Genome Project has mapped the chromosomes. Yet in that time, toilets have remained the same.

Social taboos about defecation have stymied toilet technology from evolving beyond the ceramic water closet that allowed loos to be located inside homes. Aside from some automation and digital spray control, toilet technology has remained unchanged for two centuries.

Finally in 2011, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation launched the Reinvent the Toilet Challenge to provide safe and affordable sanitation solutions to 2.5 billion people worldwide who don’t have access to toilets. The idea was to stop open defecation with a cheap alternative that would also prevent the spread of infections.

The Foundation’s specification was to re-invent the toilet that would destroy the pathogens in human waste, convert it into energy, and not need to be connected to the sewage, water, or electricity grids. And, oh yes, it should also cost less than $0.5 cents per user per day and be suitable for urban poor and rural settings.

Many companies have joined the competition with ideas like: a solar-powered toilet that generates hydrogen and electricity, sanitation systems that convert human waste into biological charcoal, fuel gas, minerals and clean water. The challenge has gained momentum in India and China where engineers are coming up with innovative new technologies.

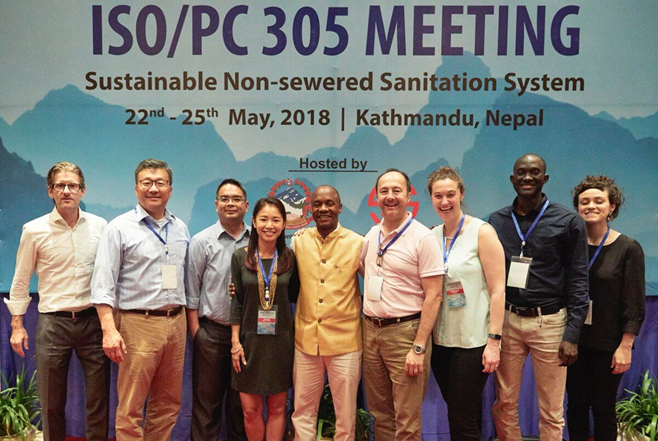

Last week, 120 experts from 33 countries were in Kathmandu to brainstorm on sustainable non-sewered sanitation systems, and approved a new standard ISO 30500 that set the requirement for toilets for the Third World that are safe, cheap and don’t need water.

“Toilets today do not work. We need a system that kills pathogens, runs off the grid, and is affordable. A structure that can operate without existing infrastructure and reach marginalised communities,” explained Doulaye Kone, sanitation expert at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The Challenge is literally a challenge. What engineers have come up with so far are contraptions ranging from what look like mini nuclear reactors to glorified pit latrines.

Kone says what the Foundation is looking for are appliances that will outwardly appear no different from existing toilets, but will be standalone structures with no sewers, and can convert waste into clean water and energy. Cost, maintenance and social acceptance will be the main hurdles to be overcome.

Manufacturers are ready to bring some of the new inventions into the market, but the ones so far are still expensive. Kone argues that while the prototypes may be expensive and will target urban dwellers, mass production of a viable business model will eventually take it to the poorest.

“This is innovative technology that allows for on-site treatment and produces minimum waste, while producing pathogen free water,” says Bipin Dangol of Environment and Public Health Organisation (ENPHO). “Its capital investment might be large, but we have a good financial mechanism and social marketing. We just need to convince people that this system will be good for the health of their families.”

Source: Nepali Times