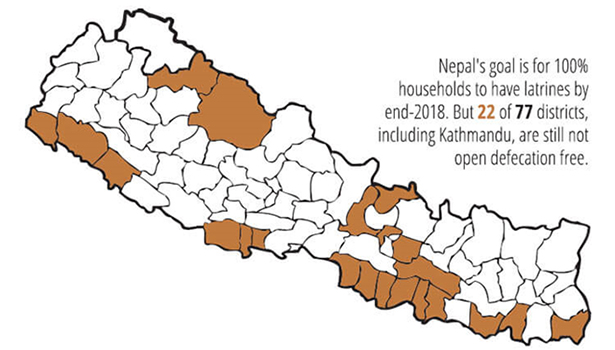

Till recently, across many parts of Nepal, where people defecated was a matter of life or death.

Sidewalks and trails strewn with human excrement spread disease and contaminated drinking water. The main killer of children in Nepal used to be diarrhoeal dehydration.

But in the past decade, the rapid spread of household latrines in Nepal is an internationally recognised success story. And it has saved the lives of many thousands of children who would otherwise have fallen victims to water-borne diseases like diarrhoea, typhoid and cholera.

There is an inverse correlation between the increase in the proportion of households with toilets and the decrease in child mortality. In 1980 only 2% of homes had toilets, that figure has jumped to 97% today. In the same period, Nepal’s under-five child mortality dived from 209 per 1,000 live births to below 35 today.

“The achievement in health outcomes of household toilets, especially in reducing diarrhoea incidence in the last five years, has been dramatic,” said Siddhi Shrestha of UNICEF.

However, experts say just declaring a district open defection free does not mean it is — access to water supply plays a critical role. In addition, the toilets need to be cleaned regularly to keep them hygienic. An evaluation found many latrines of substandard construction, not child or girl-friendly, many were located next to water sources, or were contaminating ground water. Open pits were buzzing with flies, which spread disease.

Toilets in many schools and households were so dirty many students and villagers preferred to go out into the open.

“Having a toilet in every household and declaring a district open defecation free is a major achievement. But having a toilet is different from using a toilet,” explained UN-HABITAT’s Bhushan Tuladhar.

But as Nepal inches closer to the 100% household toilet target, another danger has already manifested itself: management of excreta that is overflowing out of pit latrines and septic tanks. There are only a handful of functioning faecal sludge treatment plants, even though emptying the sewage has become a booming business.

“It is now time to think beyond the toilets,” said Bipin Dangol of Environment and Public Health Organisation (ENPHO). “Unless waste water and human excreta are safely disposed, we will continue to face health risks. The next step is to spread awareness about proper disposal of waste.”

Toilets are now being thought of as part of a value chain system, starting from user interface, containment and transportation of the waste, followed by its treatment, disposal and safe reuse.

The current toilet technology that involves flush tanks using drinking water is resource-intensive, especially in Nepal’s cities which suffer a chronic water shortage. Engineers worldwide are experimenting with the next generation of toilet designs that allow excreta to be burnt and converted into valuable energy source. They also want the new prototypes to be affordable, work off-grid so that the poorest communities have access to safe sanitation solutions (read story below).

Sanitation expert Doulaye Kone of the the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was in Kathmandu recently for a meeting to approve a new standard ISO 30500 that set requirements for toilets of the future. They have to meet many criteria: destroy waste and kill pathogens, not use water or electricity, generate energy and water, cost less than Rs5 per use, and be easy to install and maintain.

“A new toilet that meets these standards will be a super vaccine,” he told Nepali Times in an interview. “A toilet is a health product so that people won’t have to suffer or die due to the lack of safe sanitation anymore.”

A working model for a future breakthrough in Nepal’s sanitation movement could be a new facility at an orphanage in Lubhu, which treats household effluent, turning it into methane gas, fertilizer and water for the kitchen and vegetable garden.

Sanitation engineer Reetu Rajbhandari (pictured below at the Lubhu treatment plant) at ENPHO says the system is still expensive, and there are challenges of the location.

But she added: “This is an ideal solution for waste collection, disposal, treatment and recycling when everyone has a toilet. Future research needs to go into making it more affordable.”

Sanitation engineer Reetu Rajbandari at the first of its kind faecal sludge treatment plant in Lubhu. Pic: Sonia Awale.

Source: Nepali Times